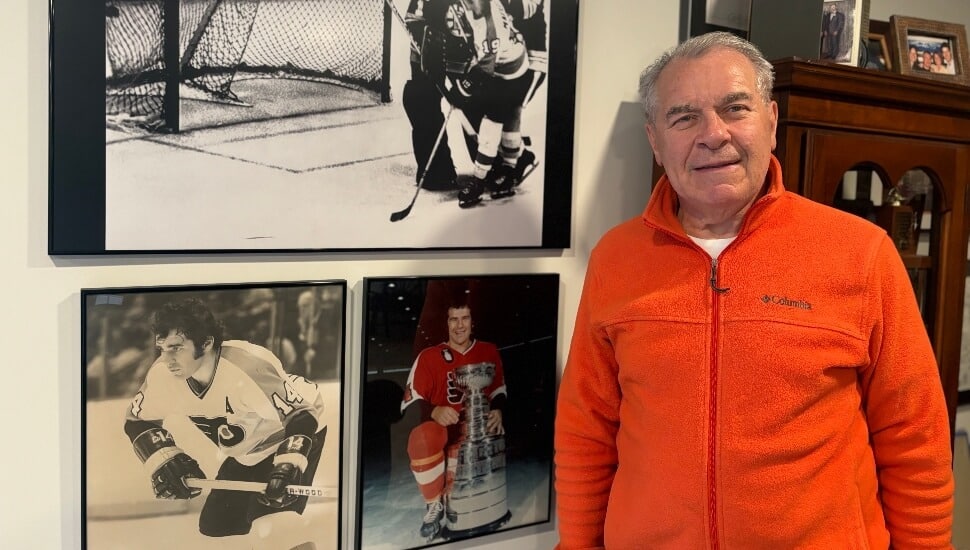

Bucks County Leadership: Joe Watson, Former Philadelphia Flyers Defenseman

Joe Watson, the former defenseman for the Philadelphia Flyers who lives in Media with his wife Jamie, spoke to BUCKSCO Today about his childhood in British Columbia as the oldest of six brothers. He discussed his love of sports, from watching his first baseball game with his cousin in Michigan to getting recruited for the Estevan Bruins hockey team.

Watson recalls moving to Philadelphia after playing for several other major and minor league hockey teams. He talked about influential coaches throughout his career, the Flyers’ Stanley Cups win in 1974, his new book and the advice from his parents that he’s always lived by.

Where were you born and where did you grow up?

I was born and raised in Smithers, British Columbia, which is 750 miles northwest of Vancouver and 150 miles southeast of Alaska. It’s up there, but boy, it’s a beautiful area. There’s a big valley with hunting and fishing and scenery between two mountain ranges, the Hudson Bay Mountains and the Babine Mountains.

What did your parents do?

My dad was a butcher in the wintertime, and he worked in a logging mill in the summertime.

My mother had a little restaurant for a while, and she waitressed for various people. She also took care of chickens, horses, and pigs.

Where were you in the pecking order?

I was the oldest of six boys.

A lot of testosterone around that dinner table.

Oh my god, yeah. I remember, as a young boy, having my cereal, and I’d have the cereal box around me so my brothers couldn’t see what I was eating. Every once in a while, they’d sneak over and try to see what I was eating, and I’d punch them.

What other memories stay with you from growing up in Smithers?

When I’d ride my bike, I’d take my little fishing pole, go 5 or 6 or 7 miles out of town and try to catch some fish. I’d bring three or four rainbow trout back, and my mom was always happy about that. We would clean them and have fish for the evening.

I loved baseball. In 1953, my mother said, “We’re going to go down and visit our relatives in Bessemer, Michigan.” We took a seven-day train ride down there in July, and it was hotter than the hinges of hell. My cousin Jimmy said, “Do you like to watch baseball?” We watched the St. Louis Browns against the Detroit Tigers on a black-and-white television, and that’s how I became a Detroit fan. All sports of Detroit – the Lions should have won that game this year.

Did you have any part-time jobs while you were growing up?

As a young boy, I had a little toboggan, and when I wanted to make some money in the wintertime, I’d take orders for Christmas trees. I’d get my little saw and my toboggan and go cut these trees down, and I’d sell them for a dollar apiece. I’d get $50 to buy Christmas presents with.

I also helped clean the local theater. It was called the Rio Theater and had about 300 seats. I got 75 cents every time I swept the theater. Mrs. Buchanan, who owned the theater, hired me to cut her wood and bring it in every day. She’d give me 25 cents a week, and I thought I was in hillbilly heaven.

Then, I got a little more serious about sports, and I started working in a lumber mill when I was about 14 years old. The lumber mill was a tough workout. You’d have these logs come in and you’d try to decide how long the lumber should be, anywhere from 10 feet to 18 feet. This is wet lumber. You had to pull the lumber off the green chain and pile it. That was very intense, hard work, but I enjoyed it because it was good for my arms and shoulders.

You had a real work ethic as a young kid. Where did that come from?

My mother instilled that in us. “You don’t get anything for nothing – you’ve got to earn everything.” I never forgot those words.

Tell me about the music you liked as a teenager and young adult.

I liked the Supremes and the Righteous Brothers in the ‘60s. Like any young person growing up, I loved to listen to music. I had a shortwave radio, so I listened to various kinds of music, but it had to be something with some pizzazz in it. Harry Belafonte and Dean Martin and those guys – I got to know Bobby Rydell very well when Bobby was in Philadelphia. And I remember when Elvis first came out in the ‘50s, Jailhouse Rock and all that.

Who saw promise in you when you were starting your sports career?

When I was around 14 to 16, our hockey team went to the finals. We didn’t know there was a scout from the Boston Bruins there. He came down to the dressing room, introduced himself, and said that he was interested in three of our players, one being me.

What did he see in you, Joe?

I think he saw my intestinal fortitude. I wasn’t as talented as a lot of my teammates, especially when I played pro hockey. But I never gave up and I worked very hard at whatever I tried to accomplish.

Who else saw promise in you as a player?

There was a guy named Joe Tenant. He was a railroad engineer in Smithers. He moved there in 1957 and became our hockey coach. When we got scouted, he was the one who drove me down to the Estevan Bruins’ training camp in 1960. It’s 2,800 miles away from where we’re from – it took us five days to get there. Most of the roads were gravel roads.

So, I get down there, and there’s 104 guys trying out for four positions on the team. I went to the scout and said, “Why did you invite me?” He said, “Joey, if I didn’t think you had a chance, I wouldn’t have invited you.” That’s all I had to hear. I had to go there and prove myself, by hook or by crook, so I said, “Well, jeez, I’m going to get in three or four fights.” And I got in three or four fights. I don’t think I won a single one. Five days later, there’s a hundred guys gone and I’m still there, and that’s the start of my career.

I remember they asked me to sign a contract, and I said, “That means you’re going to pay me?” I made $150 a month and $120 went to room and board, so that meant I had $30 to spend every month, and I was living high on the hog.

So, how did you get to Philadelphia? What did you think when you ended up in a trade?

I had two good years in the minors with Minneapolis and Oklahoma City, when they moved the franchise there. Harry Sinden was my coach. I had a real good year there. We won the league championship and I was named to the first all-star team, which was nice. I got a $500 bonus for that.

Then, in 1966, I went to training camp and met Bobby Orr. Lo and behold, we both made the team together and we lived together in Little Nahant, a small town outside of Boston.

Bobby Orr was a defenseman, too, wasn’t he?

He was. He probably revolutionized defense. He was powerful. I met him in 1965 in London, Ontario – that’s where they had their training camp. He was about 135 or 140 pounds. I said, “How can he be a hockey player? He’s not big enough.”

Well, he went back to Junior hockey and bought a rowing machine. He used to row three or four days a week, two to three hours a day. When I met him the next year, he was 190 pounds of muscle. I couldn’t believe he was the same guy. So then he starts gallivanting around the ice. He was wonderful to watch – I’m just glad I didn’t have to play against him, although I did later in my career.

In June of ’67, I got picked by Philadelphia. I had played for Boston the year before and had a good year there. In those days, you were allowed to protect 10, and the rest of the players were available. Talk about disappointment. But in a way, coming to Philadelphia was the best thing that ever happened to me.

In the first year, you gelled as a team.

We did. Ed Snider, the owner, bought the Quebec franchise from the Montreal Canadiens. I think they paid $1 million for the franchise. They had five or six players that could play in the NHL, but they were owned by Montreal, and Montreal was so loaded with players that they didn’t need them. They were instrumental in our success the first year. Our team did very well against the other six established teams that year.

Then we had to play St. Louis in the playoffs. They were a big, physical team, and they beat us in seven games. Mr. Snider vowed this would never happen to another Flyers team. The Broad Street Bullies were in our infancy – it took three or four years to get the team gelled into a good, physical team. But Mr. Snider instructed the scouts and the general manager, Bud Poile, that he wanted a physical team, so he drafted Dave Schultz, Don Saleski, and Bob Kelly.

What’s your favorite memory from your time with the Flyers? Do you have a favorite game?

My favorite game, obviously, was the Stanley Cup Finals in 1974 when we won our first Stanley Cup. I was on the ice when Orr shot the puck down. It went behind the net, and of course, when I got to the puck, I wasn’t going to touch it because it would have been icing. With four seconds left, a guy named Wayne Cashman came sliding into me and I touched the puck. The ref blew the whistle, but there was so much noise in the building that the timekeeper didn’t hear the bloody whistle. So, a centerman named Terry Crisp – the game was over, and I thought there were still four seconds to go – Crispy jumped off the bench and skated toward the linesmen, and grabbed the puck from the ref. Crisp still has that puck today; he won’t give it up!

What did you do when you got done with your hockey career? You had a great reputation.

When I was with the Flyers in 1978, I had my year-end meeting with the coach and the general manager. The Flyers came to me and said, “Joe, we want to start developing young defensemen. We’d like to keep you here to play 35 or 40 games.” I told them, “Heck, I want to play – I don’t want to sit around.” They said, “If that’s the case, we’re going to have to trade you.” They traded me to the Colorado Rockies. When I went out to Colorado, I was named the captain of the team. They were a young team.

I played my first game as a professional in 1963 in the old St. Louis arena, and I played my last game on November 11, 1978, in the same building. I went to the boards to retrieve the puck in the second period. I stretched out to reach for it, the St. Louis player pushed my lower back and I broke my right leg in 13 places. That was the end of my career.

So, what are you focused on now, Joe?

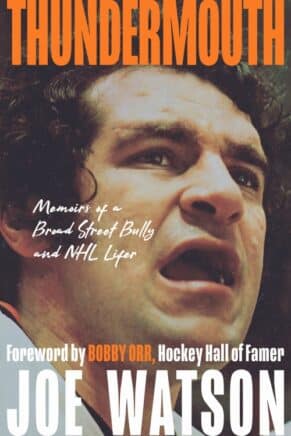

I’m keeping busy with this book I’ve got out, Thundermouth. I’ve sold about 3,000 copies in a month, and I’ve got another 3,000 to 4,000 to sell. I’ve sent some to Canada, some to Australia, a couple of books to Budapest, Hungary. It’s the power of the internet.

And I play a lot of golf in the summertime.

What is somebody going to find out about you in the book that they might not know otherwise?

When I was 16 or 17, I played in the B.C. junior baseball championships in Victoria, British Columbia. I was recruited by a team in our league – you were allowed to bring three players from your league on the team. I went down there and hit the heck out of the ball. There was a Yankee scout there – I think his name was Eddie Taylor from the Seattle league. He came down to our dressing room after we finished. He approached me and asked if I’d be interested in playing baseball. I said, “I love baseball, but there are too many good American kids. I just don’t think I’d have a chance.” He said, “Well, I’d like to invite you if you’d be interested.” I said, “Well, I’m going to Estevan, Saskatchewan, to try out for a junior league team. If I don’t have any success, I’ll approach you.” But I made it, and that was it. But I never forgot about baseball. I always played baseball in the summertime.

Three final questions, Joe. What’s something you’ve changed your mind about over the past 10 or 15 years?

We went to Russia five years ago to play some games in Russia, and we took a reporter named Bill Meltzer with us. He works for the Flyers. I decided that if I ever did a book, I wanted to get him to write the book. My wife, Jamie, said, “You should do a book. You have so many great stories.” She wasn’t the only one who told me this, and one day I decided that I’m going to write a book. Initially, I wasn’t going to do it, but I changed my mind when we went to Russia and had such a great following on our team.

It’s a crazy world out there, Joe. What keeps you hopeful and optimistic?

Oh boy, oh boy, oh boy. Well, I hope we can get the world straightened away so we can start living a normal life again. It’s not a normal world that we’re used to. There are so many changes going on. You know, if you follow the Bible – I don’t follow the Bible that closely, but I go to church – and the Bible predicts that the end of the world is coming, but we don’t know when. But all the stuff that’s going on right now, I can see what the Bible means by that. It’s crazy. We’ve got to change this world around soon, or there will be no world, eventually.

Finally, Joe, what’s the best advice you ever received?

My dad and mom had an influence on me. They taught me that nothing is given – you’ve got to go earn it. I’ve always felt that way. It’s very important to me. If you want it, you go earn it. That’s what I try to do, and it’s worked out well for myself.

__________

Connect With Your Community

Subscribe for stories that matter!

"*" indicates required fields